Reparations for slavery debate in the United States

Reparations for slavery is a proposal that some type of compensation should be provided to the descendants of enslaved people in the United States, in consideration of the coerced and uncompens

ated labor their ancestors performed over centuries. This compensation has been proposed in a variety of forms, from individual monetary payments to land-based compensation schemes related to independence. The idea remains highly controversial and no broad consensus exists as to how it could be implemented. There have been similar calls for reparations from some Caribbean countries[1] and elsewhere in the African diaspora, and some African countries have called for reparations to their states for the loss of their population.[2][3]

U.S. historical context[edit]The arguments surrounding reparations are based on the formal discussion about many different reparations and actual land reparations received by African-Americans which were later taken away. In 1865, after the Confederate States of America were defeated in the American Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Orders, No. 15 to both "assure the harmony of action in the area of operations"[4] and to solve problems caused by the masses of freed slaves, a temporary plan granting each freed family forty acres of tillable land in the sea islands and around Charleston, South Carolina for the exclusive use of black people who had been enslaved. The army also had a number of unneeded mules which were given to settlers. Around 40,000 freed slaves were settled on 400,000 acres (1,600 km²) in Georgia and South Carolina. However, President Andrew Johnson reversed the order after Lincoln was assassinated and the land was returned to its previous owners. In 1867, Thaddeus Stevens sponsored a bill for the redistribution of land to African Americans, but it was not passed.

Reconstruction came to an end in 1877 without the issue of reparations having been addressed. Thereafter, a deliberate movement of regression and oppression arose in southern states. Jim Crow laws passed in some southeastern states to reinforce the existing inequality that slavery had produced. In addition white extremist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan engaged in a massive campaign of intimidation throughout the Southeast in order to keep African Americans in their prescribed social place. For decades this assumed inequality and injustice was ruled on in court decisions and debated in public discourse.

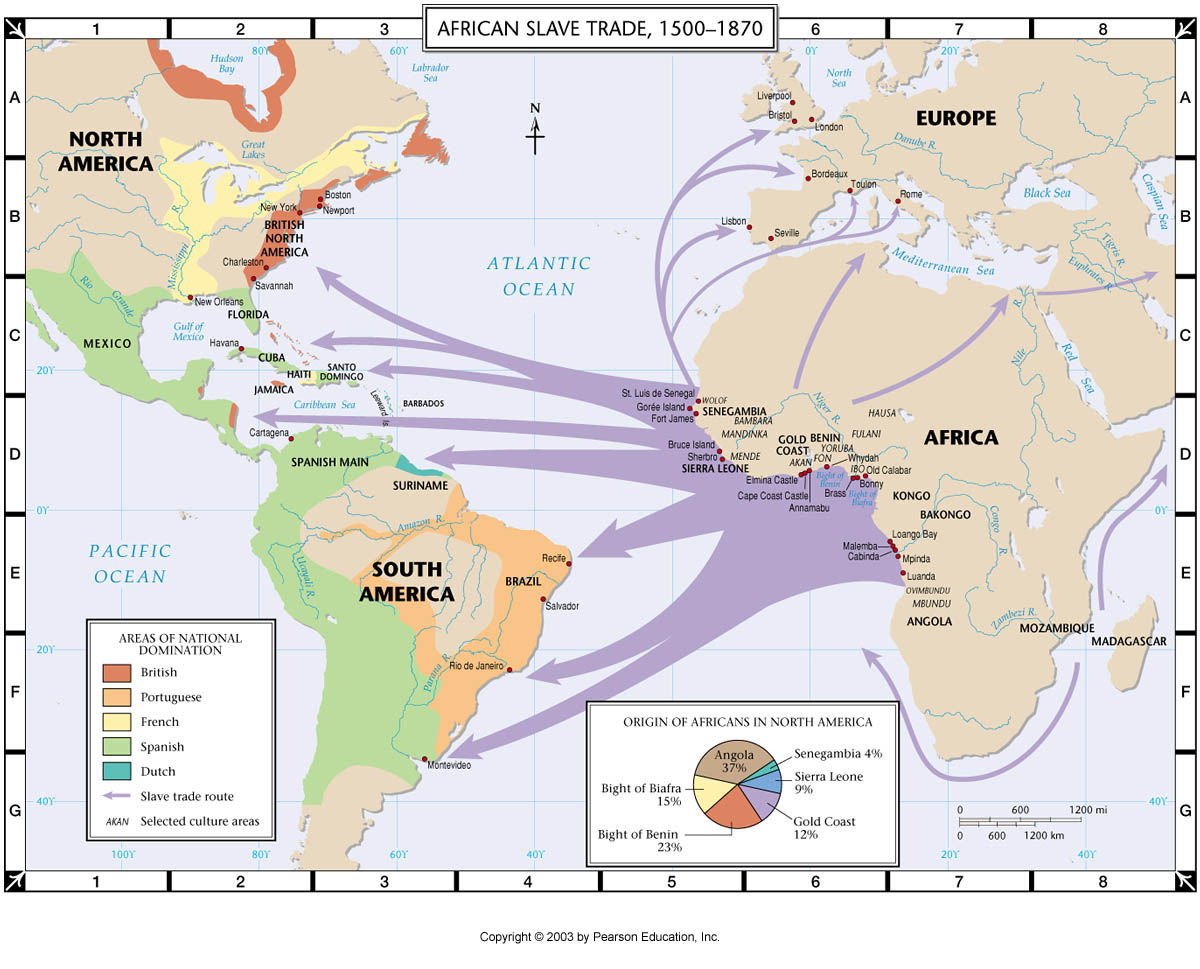

Reparation for slavery in what is now the United States is a complicated issue. Any proposal for reparations must take into account the role of the, then relatively newly formed, United States government in the importation and enslavement of Africans and that of the older and established European countries that created the colonies in which slavery was legal; as well as their efforts to stop the trade in slaves. It must also consider if and how much modern Americans have benefited from the importation and enslavement of Africans since the end of the slave trade in 1865. Profit from slavery was not limited to a particular region: New England merchants profited from the importation of slaves, while Southern planters profited from the continued enslavement of Africans. In a 2007 column in The New York Times, historian Eric Foner writes:

[In] the Colonial era, Southern planters regularly purchased imported slaves, and merchants in New York and New England profited handsomely from the trade.

The American Revolution threw the slave trade and slavery itself into crisis. In the run-up to war, Congress banned the importation of slaves as part of a broader nonimportation policy. During the War of Independence, tens of thousands of slaves escaped to British lines. Many accompanied the British out of the country when peace arrived.

Inspired by the ideals of the Revolution, most of the newly independent American states banned the slave trade. But importation resumed to South Carolina and Georgia, which had been occupied by the British during the war and lost the largest number of slaves.

The slave trade was a major source of disagreement at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. South Carolina’s delegates were determined to protect slavery, and they had a powerful impact on the final document. They originated the three-fifths clause (giving the South extra representation in Congress by counting part of its slave population) and threatened disunion if the slave trade were banned, as other states demanded.

The result was a compromise barring Congress from prohibiting the importation of slaves until 1808. Some Anti-Federalists, as opponents of ratification were called, cited the slave trade clause as a reason why the Constitution should be rejected, claiming it brought shame upon the new nation....

As slavery expanded into the Deep South, a flourishing internal slave trade replaced importation from Africa. Between 1808 and 1860, the economies of older states like Virginia came increasingly to rely on the sale of slaves to the cotton fields of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. But demand far outstripped supply, and the price of slaves rose inexorably, placing ownership outside the reach of poorer Southerners.[5]

Proposals for reparations[edit]United States government[edit]Some proposals have called for direct payments from the U.S. government. One such proposal delivered in the McCormick Convention Center conference room for the first National Reparations Convention by Howshua Amariel, a Chicago social activist, would require the federal government to make reparations to proven descendants of slaves. In addition, Amariel stated "For those blacks who wish to remain in America, they should receive reparations in the form of free education, free medical, free legal and free financial aid for 50 years with no taxes levied," and "For those desiring to leave America, every black person would receive a million dollars or more, backed by gold, in reparation." At the convention Amariel's proposal received approval from the 100 or so participants,[6] nevertheless the question of who would receive such payments, who should pay them and in what amount, has remained highly controversial,[7][8] since the United States Census does not track descent from slaves or slave owners and relies on self-reported racial categories.

Various estimates have been given if such payments were to be made. Harper's Magazine has created an estimate that the total of reparations due is over 100 trillion dollars, based on 222,505,049 hours of forced labor between 1619 and 1865, with a compounded interest of 6%.[9] Should all or part of this amount be paid to the descendants of slaves in the United States, the current U.S. government would only pay a fraction of that cost, over 40 trillion dollars, since it has been in existence only since 1789.

The Rev. M.J. Divine, better known as Father Divine, was one of the earliest leaders to argue clearly for "retroactive compensation" and the message was spread via International Peace Mission publications. On July 28, 1951, Father Divine issued a "peace stamp" bearing the text: "Peace! All nations and peoples who have suppressed and oppressed the under-privileged, they will be obliged to pay the African slaves and their descendants for all uncompensated servitude and for all unjust compensation, whereby they have been unjustly deprived of compensation on the account of previous condition of servitude and the present condition of servitude. This is to be accomplished in the defense of all other under-privileged subjects and must be paid retroactive up-to-date".[10]

On July 30, 2008, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution apologizing for American slavery and subsequent discriminatory laws.[11]

Some states have also apologized for slavery, including Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. Duke University public policy professor William "Sandy" Darity said such apologies are a first step, but compensation is also necessary.

In April 2010, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates in a New York Times editorial advised reparations activists to consider the African role in the slave trade in regards to who should shoulder the cost of reparations.[12]

Ex-colonial governments

The full cost of slavery reparations prior to 1776 would be borne by the governments of the European countries (Spain, the United Kingdom, and France) who governed North America at that time[why?]. One additional problem is that the governments in power in the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe are not still in power now. France, for example, has gone through several forms of government since it was last a colonial power in North America. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to hold the current French government liable for the enslavement of Africans that previous governments encouraged and benefited from between the 17th century up to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Private institutions[edit]Private institutions and corporations were also involved in slavery. On March 8, 2000, Reuters News Service reported that Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, a law school graduate, initiated a one-woman campaign making a historic demand for restitution and apologies from modern companies that played a direct role in enslaving Africans. Aetna Inc. was her first target because of their practice of writing life insurance policies on the lives of enslaved Africans with slave owners as the beneficiaries. In response to Farmer-Paellmann's demand, Aetna Inc. issued a public apology, and the "corporate restitution movement" was born.[not specific enough to verify]

By 2002, nine lawsuits were filed around the country coordinated by Farmer-Paellmann and the Restitution Study Group—a New York non-profit. The litigation included 20 plaintiffs demanding restitution from 20 companies from the banking, insurance, textile, railroad, and tobacco industries. The cases were consolidated under 28 U.S.C. § 1407 to multidistrict litigation in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. The district court dismissed the lawsuits with prejudice, and the claimants appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

On December 13, 2006, that Court, in an opinion written by Judge Richard Posner, modified the district court's judgment to be a dismissal without prejudice, affirmed the majority of the district court's judgment, and reversed the portion of the district court's judgment dismissing the plaintiffs' consumer protection claims, remanding the case for further proceedings consistent with its opinion [1]. Thus, the plaintiffs may bring the lawsuit again, but must clear considerable procedural and substantive hurdles first:

If one or more of the defendants violated a state law by transporting slaves in 1850, and the plaintiffs can establish standing to sue, prove the violation despite its antiquity, establish that the law was intended to provide a remedy (either directly or by providing the basis for a common law action for conspiracy, conversion, or restitution) to lawfully enslaved persons or their descendants, identify their ancestors, quantify damages incurred, and persuade the court to toll the statute of limitations, there would be no further obstacle to the grant of relief.[13]

In October 2000, California passed a Slavery Era Disclosure Law requiring insurance companies doing business there to report on their role in slavery. The disclosure legislation, introduced by Senator Tom Hayden, is the prototype for similar laws passed in 12 states around the United States.[citation needed]

The NAACP has called for more of such legislation at local and corporate levels. It quotes Dennis C. Hayes, CEO of the NAACP, as saying, "Absolutely, we will be pursuing reparations from companies that have historical ties to slavery and engaging all parties to come to the table."[14] Brown University, whose namesake family was involved in the slave trade, has also established a committee to explore the issue of reparations. In February 2007, Brown University announced a set of responses[15] to its Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice.[16] While in 1995 the Southern Baptist Convention apologized for the "sins" of racism, including slavery.[17]

In December 2005, a boycott was called by a coalition of reparations groups under the sponsorship of the Restitution Study Group. The boycott targets the student loan products of banks deemed complicit in slavery—particularly those identified in the Farmer-Paellmann litigation. As part of the boycott students are asked to choose from other banks to finance their student loans."[18]

In 2005, JP Morgan Chase and Wachovia both apologized for their connections to slavery

Social services

A number of supporters for reparations[who?] advocate that compensation should be in the form of community rehabilitation and not payments to individual descendants

Arguments for reparations

Accumulated wealth[edit]In 2008 the American Humanist Association published an article which argued that if emancipated slaves had been allowed to possess and retain the profits of their labor, their descendants might now control a much larger share of American social and monetary wealth.[21] Not only did the freedmen and -women not receive a share of these profits, but they were stripped of the small amounts of compensation paid to some of them during Reconstruction. The wealth of the United States, they say, was greatly enhanced by the exploitation of African American slave labor.[22] According to this view, reparations would be valuable primarily as a way of correcting modern economic imbalance.

Precedents[edit]Under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, the U.S. government apologized for Japanese American internment during World War II and provided reparations of $20,000 to each survivor, to compensate for loss of property and liberty during that period. For many years, Native American tribes have received compensation for lands ceded to the United States by them in various treaties. Other countries have also opted to pay reparations for past grievances, such as the German government making reparations to Jews and survivors and descendants of the Holocaust.[23]

Arguments against reparations[edit]Relocation of injustice[edit]The principal argument against reparations is that their cost would not be imposed upon the perpetrators of slavery who were a very small percentage of society with 4.8% of southern whites (only 1.4% of all whites in the country)[citation needed], nor confined to those who can be shown to be the specific indirect beneficiaries of slavery, but would simply be indiscriminately borne by taxpayers per se. Those making this argument often add that the descendants of white abolitionists and soldiers in the Union Army might be taxed to fund reparations despite the sacrifices their ancestors already made to end slavery.

In the case of Public Lands, European colonizers killed or forcibly relocated[24] many Southeastern Native American tribes. One argument against reparations is that in assigning public lands to African-Americans for the enslavement of their ancestors, a greater and further wrong would be committed against the Southeastern Native Americans[25] who have ancestral claims and treaty rights to that same land.[not specific enough to verify]

In addition, several historians, such as João C. Curto, have made important contributions to the global understanding of the African side of the Atlantic slave trade. By arguing that African merchants determined the assemblage of trade goods accepted in exchange for slaves, many historians argue for African agency and ultimately a shared responsibility for the slave trade.[26]

Identification of victims and of levels of victimization[edit]Identification of actual descendants of slaves would be an enormous undertaking, because such descent is not simply identical with present racial self-identification. And levels of actual victimization would be impossible to identify; had freed slaves been given their recoverable damages, they may have followed different patterns of marriage and of reproduction, and in some cases would not have made their offspring the sole or even principal heirs to their estates. (Opponents of reparations refer to the lost wealth of slaves as “dissipated”, not in the sense of simply having ceased to exist, but in the sense of being untraceable and transmitted elsewhere.)[citation needed]

Comparative utility[edit]It has been argued that reparations for slavery cannot be justified on the basis that slave descendants are subjectively worse off as a result of slavery, because it has been suggested that they are better off than they would have been in Africa if the slave trade had never happened. The slave population in the US grew six-fold after the importation of slaves was ceased. In all other countries the slave population either did not increase or declined. This was because the treatment of slaves in the US was generally very good - birth survival rates exceeded that of poor whites and was twice that of their native Africa. In addition, each state had laws against the abuse of slaves and many religious groups rigorously enforced them.

In Up From Slavery, former slave Booker T. Washington wrote,

I have long since ceased to cherish any spirit of bitterness against the Southern white people on account of the enslavement of my race. No one section of our country was wholly responsible for its introduction... Having once got its tentacles fastened on to the economic and social life of the Republic, it was no easy matter for the country to relieve itself of the institution. Then, when we rid ourselves of prejudice, or racial feeling, and look facts in the face, we must acknowledge that, notwithstanding the cruelty and moral wrong of slavery, the ten million Negroes inhabiting this country, who themselves or whose ancestors went through the school of American slavery, are in a stronger and more hopeful condition, materially, intellectually, morally, and religiously, than is true of an equal number of black people in any other portion of the globe....This I say, not to justify slavery – on the other hand, I condemn it as an institution, as we all know that in America it was established for selfish and financial reasons, and not from a missionary motive – but to call attention to a fact, and to show how Providence so often uses men and institutions to accomplish a purpose. When persons ask me in these days how, in the midst of what sometimes seem hopelessly discouraging conditions, I can have such faith in the future of my race in this country, I remind them of the wilderness through which and out of which, a good Providence has already led us.[27]

Conservative commentator David Horowitz writes,

The claim for reparations is premised on the false assumption that only whites have benefited from slavery. If slave labor created wealth for Americans, then obviously it has created wealth for black Americans as well, including the descendants of slaves. The GNP of black America is so large that it makes the African-American community the 10th most prosperous "nation" in the world. American blacks on average enjoy per capita incomes in the range of twenty to fifty times that of blacks living in any of the African nations from which they were taken.[28]

Legal argument against reparations[edit]Many legal experts point to the fact that slavery was not illegal in the United States[29] prior to the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (ratified in 1865). Thus, there is no legal foundation for compensating the descendants of slaves for the crime against their ancestors when, in strictly legal terms, no crime was committed. Chattel slavery is now considered by the overwhelming majority in the United States to be highly immoral, though it was perfectly legal at the time. However, opponents of this legal argument contend that such was the case in Nazi Germany, whereby the activities of the Nazis were legal under German law; however, unlike slavery, the German activities were precedented by the Allied Powers following WWI, which could not rule against the German government then due to lack of precedent, but could do so afterward following WWII on the basis of this established WWI precedent.

Other legal experts[who?] point to the fact that the current U.S. government did not exist prior to June 21, 1788 when the United States Constitution was ratified. Therefore, they say the U.S. government inherited the institution of slavery, and cannot be held legally liable for the enslavement of Africans by Europeans prior to that time. Figuring out who was enslaved by whom in order to fairly apply reparations from the U.S. government only to those who were enslaved under U.S. laws, would be an impossible task.

Some areas of the South had communities of freedman, such as existed in Savannah, Charleston and New Orleans, while in the North, for example, former slaves lived as freedman both before and after the creation of the United States in 1788. For example, in 1667 Dutch colonists freed some of their slaves and gave them property in what is now Manhattan.[30][31] The descendants of Groote and Christina Manuell—two of those freed slaves—can trace their family's history as freedman back to the child of Groote and Christina, Nicolas Manuell, whom they consider their family's first freeborn African-American. In 1712, the British, then in control of New York, prohibited blacks from inheriting land, effectively ending property ownership for this family. While this is only one example out of thousands of enslaved persons, it does mean that not all slavery reparations can be determined by racial self-identification alone; reparations would have to include a determination of the free or slave status of one's African-American ancestors, as well as when and by whom they were enslaved and denied rights such as property ownership. Because of slavery, the original African heritage has been blended with the American experience, the same as it has been for generations of immigrants from other countries. For this reason, determining a "fair share" of reparations would be an impossible task.

Another legal argument against reparations for slavery from a legal (as opposed to a moral standpoint) is that the statute of limitations for filing lawsuits has long since passed. Thus, courts are prohibited from granting relief. This has been used effectively in several suits, including "In re African American Slave Descendants", which dismissed a high-profile suit against a number of businesses with ties to slavery.[citation needed]

Another argument against reparations (though this is not a legal argument) is that few African-Americans are of "pure" African blood since the offspring of the original slaves were occasionally the progeny of Caucasian male masters (and a variety of White males) by means of rape, concubinage or threat and forcibly slave-breeding of African female slaves.[dubious – discuss]

Reparations could cause increased racism[edit]Anti-reparations advocates argue reparations payments based on race alone would be perceived by nearly everyone as a monstrous injustice, embittering many, and inevitably setting back race relations. In this view, apologetic feelings some whites may hold because of slavery and past civil rights injustices would, to a significant extent, be replaced by anger.[citation needed]

The Libertarian Party, among other groups and individuals, has suggested that reparations would make racism worse:

A renewed demand by African-Americans for slavery reparations should be rejected because such payments would only increase racial hostility...[32]

A leading work against reparations is David Horowitz, Uncivil Wars: The Controversy Over Reparations for Slavery (2002). Other works that discuss problems with reparations, include John Torpey, Making Whole What Has Been Smashed: On Reparations Politics (2006), Alfred Brophy, Reparations Pro and Con (2006), Nahshon Perez, Freedom from Past Injustices (Edinburgh University Press, 2012).

There is also a technical problem with identifying those who should be entitled to exemptions because of their ancestral opposition to Slavery. In particular, there was a significant Anti-Slavery Resistance Movement among the German and Mexican Texans during the Civil War [2] which effectively negated the gains from New Mexico [3] by choking off supplies.